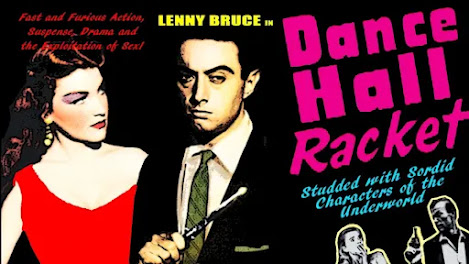

Dance Hall Racket

A decade before succumbing to the poisoned fame that came with being America’s most controversial stand-up comedian, Lenny Bruce flirted with the movies, co-writing the harmless sci-fi comedy The Rocket Man (1953), about a boy who is gifted a special gun by an alien which when fired, compels its target to tell the truth. The film did average business at the box office and soon vanished from memory.

A few months after the dubious privilege of making one of the worst sci-fi movies ever made, Robot Monster (1953), director Phil Tucker, recovering from a mental breakdown after being duped from his share of the film’s remarkably healthy profits, pondered his return to Hollywood, while his recent creation awaited immortality as one of cinema’s most beloved of bad movies.

What happens when unstoppable genius meets an unmovable hack?

Fate supplied the answer when Bruce and Tucker struck up a friendship while rooting through the metaphorical garbage cans of Poverty Row looking for work. Luckily for both, one sub-genre of film was enjoying its final bloom, a kind of film that as far as quality was concerned, required nothing more than mediocrity aside from assets neither the director or comedian could supply themselves, for women were the stars of films which had their roots in America of a century past – the burlesque movies.

Burlesque films had their heyday in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and were often little more than replications of stage burlesque, showcasing the routines of the best known ‘exotic dancers’ of the day, such as Lili St Cyr, Tempest Storm, Evelyn West and Marsha Lane. With no need to worry over competition from TV, and with a ready-made audience of men expecting more spice from life having served in the war, such films almost always turned a profit. Soldiers had become familiar with ‘racy’ pin-ups or plane art featuring Betty Page, Gypsy Rose Lee and company as an acceptable way of boosting morale, and depending where in the world they served, men were used to the idea of strip shows and so flocked to the less salubrious theaters in town to watch the likes of Hollywood Burlesque (1948), Midnight Frolics (1949) and Side-Streets of Hollywood (1952). A few burlesque films dodged accusations of indecency by tapping into that perennial source of American comfort, the ‘good old days,’ advertising themselves as the sort of show enjoyed by their fathers or grandfathers, this despite the city of New York, to name just one example, banning all burlesque shows from its theaters in 1937 for fear of spreading vice.

Burlesque films sometimes added a linking narrative to the invariable scenes of striptease acts, lame comics and band numbers, and Tucker and Bruce combined all three to concoct Dance Hall Racket, a film with a foot both in burlesque and the sub-noir ‘social corruption’ films such as The Phenix City Story (1955) and He Lived by Night (1948). Tucker directed, while Bruce wrote the screenplay and portrayed the character of Vincent, the film’s psychotic bad guy. Producing was George Weiss, one of the kings of exploitation cinema, frequently marketing morally dubious content by claiming an educational value (as with Ed Wood’s Glen or Glenda [1953]), or exposing the sort of scam or scandal supposedly proliferating throughout the US at the time. Such scams, or ‘rackets,’ often involved a suspect but legal establishment operating as cover for illegal activity, and in DHR‘s case, it’s a nightclub being used as a front for fencing smuggled diamonds.

After the credits play under theme music more in keeping with a Looney Tunes cartoon, we open in the office of a police department, though it could be the waiting room at your local chiropractor’s for all the realism this film offers. A journalist is writing a gripping feature on police customs and excise, and needs one more story for his article. Boy, imagine the excitement if our film had centered on the story the cops had told the journalist before we joined them. As it is, we make do with a lame flashback saga instead, filled with scenes the policemen telling the story couldn’t possibly know of, and full of inconsequential details no journalist worth their bourbon would include in their article. I’m laying my cards on the table here – I’ve watched a lot of trash in my time, but the opening scene of DHR is as shabbily acted as I’ve ever witnessed in a Hollywood film, with the plain clothes cop who replies “the dance hall racket may interest you,” acting like a scarecrow operated by hidden prairie dogs talking through a muffled megaphone.

We relocate to a corner of Scalli’s Dance Emporium, a nightclub where an evening’s entertainment is in full swing. Get used to this corner, as aside from the world’s smallest bar, it serves as the setting for almost the entire club. A couple go through a set of dance moves I’ve termed The Jumping Jacks, The Tangled Marionettes and The Nodding Wooden Birds as other patrons applaud mutely. The MC breaks up this happy scene with news of the “half price seamen’s dance next Friday.” In case you’re wondering if this is an important plot point, it isn’t, and nor is the MC telling his audience “now go get a drink, the bar needs the money.”

Don’t all rush at once though, as the sole barman, stood in front of a row of drinks most LaLaFilm contributors could down during a ‘coffee break,’ is engaged in rhubarb talk with a customer. The film’s comic relief – and I remind you this film is written by Lenny Bruce – uses this distraction to help himself to free drinks. This gurning clot is Punchy (Bernie Jones), a ‘comedy Swede’ in the ‘Sven and Ole’ tradition. We’ll meet him again quite soon. May God have mercy on our souls.

A customer and one of the club’s hostesses are getting friendly and decide to take a “trip to Hawaii.” Don’t get excited, as DHR doesn’t venture much further than Phil Tucker can physically move the camera. A ‘trip to Hawaii’ involves the barman moving a potted palm in front of a table so a patron and hostess can make out in relative privacy. That’s all the ambition most of the characters, and DHR itself, exhibit; remember Robot Monster had Phil Tucker destroy the world’s population with a bubble machine perched on a rickety wooden table in Bronson Canyon; props and set design aren’t at the heart of his work.

We venture all the way upstairs and meet Umberto Scalli, played with world-weary slickness by Poverty Row denizen Timothy Farrell. This is the third movie for Farrell’s Scalli, previously appearing in The Devil’s Sleep (1949) and Racket Girls (1951, and featured in a 1994 Mystery Science Theater 3000 show). What’s more unusual is Scalli got killed at the end of Racket Girls, but has recovered from this setback. Eric Schaefer, author of Bold! Daring! Shocking! True! (1999) explains “the reuse of the same actors in the same roles meant that performers were already familiar with their characters, which would theoretically reduce, if not eliminate, the little time that might be devoted to rehearsal.” Alongside Scalli is Vincent (Lenny Bruce), his chief henchman and, oddly enough, the man with the best lines in the film.

An associate of Scalli’s, a seaman known as Ice-Pick, has smuggled diamonds from his ship for Scalli to fence. Carrying his pet dog, the man (sorry to be vague, but even IMDB struggles with naming DHR‘s cast), hid the gems from customs by sticking them onto the insides of the dog’s ears and I did not make that up. Scalli hands over $5000 but Fido’s friend objects to this evaluation. Vincent produces his own friend, a flick knife: “you want it, or you don’t want it.” “I want it!” replies the smuggler, who takes the money. After he leaves, Scalli tells Rose (Honey Harlow, a stripper and Bruce’s then-wife), a hostess, to give the man a drink, “a real good drink.”

Downstairs, the sailor asks Punchy to look after his dog for the night, sensing the Swede needs a companion of his intellectual equal. Back in the office, Vincent shows Scalli a newspaper report on the impending release from prison of a Mr Paphos, jailed for the theft of $250,000 worth of gold bullion. Scalli decides to hold a party for Mr Paphos tomorrow evening, his generosity not unconnected with the still-missing gold.

Back in the club, the smuggler turns on Rose for trying to steal the $5000 from his wallet. Vincent disables the smuggler with a lame karate chop to the neck and a less lame knife to the heart. Scalli, angry at this breach of club etiquette, tells Vincent to get rid of the body before anyone notices (luckily, no-one in the club’s other two sets witnessed this blatant murder). Scalli tells Vincent, Rose and another goon to see him in his office at once, for the performance review from hell.

However, there’s a woman waiting in Scalli’s office to give a review of her own – Fortuna, Scalli’s would-be wife. The pair discuss marriage, with Scalli sweetening a very bitter pill by telling his beloved of the hidden bullion. Scalli, Paphos’ ex-partner, intends to learn where the bullion is located and then hightail out of this crazy joint along with the $100K’s worth of diamonds he has stashed away. Fortuna is so impressed she doesn’t object to smooching with Scalli; hell, for that kind of dough I’d kiss him myself, provided I’d had the right shots.

Vincent, Rose and Ice-Pick get ticked off for their poor customer care skills. Scalli is angry, as “if people die here, no-one will buy from me anymore.” Very true; not killing your suppliers is Business 101. Scalli and Ice-Pick leave, and now it’s Vincent and Rose’s turn to talk relationships. Rose doesn’t want to become like head hostess Maxine (many a sailor’s old port in a storm, shall we say), and yearns for the security of marriage; why she’s seeking it with an obvious nutjob like Vincent is another matter. Scalli returns and tells Vincent to control his temper.

The police finally enter their own flashback (don’t they need a warrant?) and, having found the dog guy’s dead body, mull over his final possessions (including a ticket for Scalli’s club), while fending off the narcolepsy so much a scourge of this town’s law enforcers. Help is on hand in the form of Edsen, a cop drafted in from New York, determined to crack this “tough nut.”

Disguised as a sailor, Edsen arrives at Scalli’s club and buys three tickets. Instead of paying an entrance fee, customers buy tickets, each of which entitles them to one dance with a hostess and maybe sit with them a while for drinks. This deal is called the “dime-a-dance” for reasons I hope are self-explanatory. Once you’ve spent your tickets, it’s back to the bar and, if you’re lucky, Punchy will take a waltz with you for a bourbon and soda.

There follows the first of DHR‘s ‘skin scenes,’ in which women are seen topless or in a state of partial nudity. Not in the public domain version however, as a spoilsport censor has trimmed such shocking sequences, knocking three or four minutes off the already spartan running time. Here, a girl new to the club disrobes in the dressing room, before seeking advice from her new colleagues. Maxine, a calloused old hand, regales the wide-eyed gal with stories from her many, many, years of experience: a “guy gave me a diamond ring. I didn’t even have to kiss him. What a jerk!” Maxine is played by Sally Marr, Lenny’s Bruce’s mother, who must have been delighted when her son approached her with the idea of portraying an aging good-time girl.

Vincent takes a hands-on approach with the employees and sees that the new girl complies with the club’s dress code, by asking her to take off her dress (“what are you, stupid? Come on!”) and choosing duds more pleasing to the high-class clientele of the club. Once Vincent leaves, another girl helps her new colleague into the dress, and so more edits apparently achieved using garden shears.

Edsen joins Punchy and offers to buy the suspicious Swede: “No one buys Punchy a drink unless they figure they want information.” Quite true, as no-one would share the same town as Punchy unless they had a damn good reason. Edsen gets on Punchy’s good side by bluffing through a chat about ships and skippers they have known. Ice-Pick joins them, recognizing Edsen as an old shipmate. Ice-Pick tells Edsen he’ll introduce him to “the boss” tomorrow, so there’s a bit of luck.

Maxine, now looking like a furball coughed up by Phyllis Diller, demands a gin and orange from the barman, who refuses on the grounds Maxine had enough sometime during the Roosevelt administration. Scalli orders another girl to deal with Maxine, and enjoys the resulting cat-fight, another occasional attraction in the world of the burlesque film.

At last, another location! With giddiness of spirit we relocate to “Warehouse no. 1” for Edsen’s secret meeting with the police of the living dead. Edsen’s colleagues are looking to raid Scalli’s joint tomorrow night, so Edsen must gather as much information as he can, preferably not from idiot Scandinavians. We learn Ice-Pick recognized Edsen not from a ship, but a previous undercover job he worked on. Lucky for Edsen the goon possesses the same intelligence as DHR‘s key demographic (“mugs, male”).

Icepick asks Scalli if he can leave his employ to get married and take up a job in a factory. Scalli grudgingly agrees, as long as Icepick keeps his mouth shut, in a line delivered so out of view it seems to waft in from a bar across the street. Back down at one of the club’s two tables, Maxine and some schlep are bonding through a mutual love of liver disease. “I’m lousy,” insists Maxine’s new squeeze, and removes his lousy toupee to prove how lousy he is. “I still think you’re nice,” says Maxine, drinking deep from her beer goggles. Someone we assume is the mysterious Mr Paphos arrives, to judge by the Pinteresque stillness his presence brings to the club. Later, we find out this isn’t Mr Paphos at all, and it’s this scene which is the mystery.

Over in the girls’ dressing room, a blonde attempts to seduce Ice-Pick ‘because he’s there,’ but our gallant goon evades her clutches to ask Scalli if he can leave now, rather than stay on for the Paphos party. Scalli agrees, but suddenly whips out – a cash bonus for Ice-Pick for all his good work. Scalli’s an odd sort of villain, perhaps due to the wildly inconsistent writing. A case in point, the next scene, in which a man visits Scalli’s office to complain of being robbed by a hostess. Scalli demonstrates his integrity by bringing his best thug, Vincent, to knife the complainant in the stomach and throw him (unseen) in a river so close it must run directly under the floor. Vincent gloats at their efficiency: “you just dump ’em in the river and they just float off!”

Not that all the staff share Scalli’s corporate values. Lois hits the jackpot by giving a dumb drunk the old sob story about needing $70 to pay for her dear old mother’s operation. A fool and his money are easily parted and this chump would buy magic beans from a unicorn to keep dragons out of the Arctic. Scalli and Vincent shake Lois down for disobeying the house rules – if a hostess ‘scores,’ then the house gets 40%. Lois protests, so Vincent instigates a “search party,” using the same knife to hack through Lois’ blouse as the editor hacked out the scene revealing what Lois keeps inside her blouse. Slapping Lois to the floor, Scalli watches as Vincent administers a kick to the unfortunate hostess, in DHR‘s most unpleasant scene. Eventually, Lois gives up her hidden money. “I run this club like an apartment store,” explains Scalli. “If you were a clerk, you wouldn’t expect to keep all the money from everything you sold.” Adding she looks terrible, Scalli gives Lois the rest of the night off as recompense for making her look terrible.

It’s been a few minutes now since DHR introduced a superfluous comic character, so in comes another nameless buffoon who asks the barman for a “carbonated water” while spinning nervously around on his barstool. The barman serves our new friend a thimbleful, then asks why he never dances with the girls. The guy is collecting tickets – he currently has 730 – until he can afford to have the club to himself for an entire night. Every fifteen minutes would see a trip to Hawaii when, for all its exotic appeal, you might as well balance a tin of pineapple chunks on your head. “A beautiful thought,” comments the barman. “Kind of poetic…you think big.” The guy continues spinning around on his barstool, as if spreading his scent, and an uneasy pause develops as the movie tries to remember which narrative redundancy to lose itself in next.

We’re throwing some bad dice tonight, because we follow Mr 730 tickets as he takes a peek into the girls’ dressing room, where a hostess just happens to remove her clothing, allowing us a long, lingering look at her bare…back. The hostess catches our Peeping Tom in the act, and threatens to report him to Mr Scalli unless he gives up his tickets. “Now I’ll never get to go to Hawaii!” he wails, but the hostess, knowing a charity case when she sees one, gives the chump a thoroughly undeserved kiss.

DHR returns to a plot so thin it took this long for the film to find it again. Mr Paphos arrives for his homecoming surprise, after 11 years at the state penitentiary. And what a chimp’s tea party awaits him: Mr Scalli, Vincent, Punchy, Maxine, Edsen and company all boozing and grunting and one drink away from flinging their poop at each other. Edsen asks Maxine, already so addled no one dares light a match near her, why Mr Paphos is so quiet, and learns that as a result of keeping silent on the whereabouts of the bullion, some rascals cut out Paphos’ tongue, in what seems a counterproductive measure.

Scalli entertains/insults his honored guest with Maxine performing the Charleston, enough to leave any viewer with blackened frontal lobes, then presents Lois dressed in a fur stole, to erase the vision of Maxine from his mind. Time, already passing by at a crawl, goes into reverse as Punchy performs his version of a “Tahitian Love Dance,” and Tucker for once shows empathy for his audience as Scalli quietly leaves for his office, followed at a distance by Vincent.

Yep, we’ve reached the double-crossing scene. Vincent sees Scalli scoop up his secret diamonds and accuses him of “rigging up the scene back there,” a catch-all accusation enough to make anyone feel guilty. Vincent snatches away Scalli’s gun and shoots him in the stomach. Running back through the club, Vincent abducts Paphos, chased by Edsen.

Outside (at last!) in a back alley, a shoot-out sees Vincent killed by Edsen, with a little help from Paphos. With that, we end our flashback, and we’re back in the police department. “Bert’s running the club now,” explains Inspector Woodentop, “but if he slips, we’ll be after him.” “A ring-a-ring of rosies, uh?” observes the journalist, who does seem the kind of guy who filters life through nursery rhymes. “Thanks for the story, we’ve got enough now.”

And we’ve had enough now. There’s just time to watch one last dance at the club before the film collapses and ends, just before the feeble, over-used sets do likewise.

As unfair as it seems to slide such a slender slice of cheese as DHR under the microscope, it does serve to illustrate a part of contemporary American life you simply don’t get from the mainstream films and TV of the time. Life in 1953 was not The Andy Griffith Show and Doris Day musicals any more than 2015 is Two and a Half Men or Jennifer Aniston romcoms. Burlesque films are as valid a part of the postwar American experience as ‘stag’ magazines such as Man’s Life or True Men, with their lurid tales of Nazi harems, animal attacks and swingers in the suburbs. Burlesque movies served a purpose and had their time, making way for the nudism film boom of the 1960s and from then on to a greater acceptance of sexuality in general cinema.

Then again, we must also look at DHR in terms of entertainment and basic competency and here it fails on almost every level. Scenes pass by with little to do with one another, as if Lenny Bruce were playing an elaborate game of Consequences with himself in writing the script. It’s possible Bruce intended the film as a spoof, only for the clueless director to play the film straight, as happened with Queen of Outer Space (1958, written by Twilight Zone stalwart Charles Beaumont), The Incredible Melting Man (1977) and Slumber Party Massacre (1982). Whatever Bruce’s intentions, the negligible budget and Tucker’s dreary direction, with camera shots barely changing during any given scene, squash any life from the film.

The acting varies from average to dreadful. Bruce puts in the liveliest performance, delivering lines with a whip-crack, though sequences which call upon Bruce to display violence are much less effective. Wheeler Winston Dixon, in his 2015 book Dark Humor in the Films of the 1960s, comments Bruce’s “dialogue throughout DHR is delivered with the twist of a well-honed knife, with the most dramatic turns of phrase delivered as throwaway gags, as in Bruce’s nonchalant delivery of the self-scripted line ‘Big deal, I killed a guy, it just makes me a criminal.'” Dixon also described DHR as “cheap, rotten and unapologetic,” as good as reason to like a film as any.

Timothy Farrell as Umberto Scalli displays the enthusiasm of a man condemned to eat meatloaf for every meal for the rest of his life, though the more sentimental viewer may experience a twinge of sorrow when the nightclub owner is killed. The rest of the cast are just awful, but a special mention goes to Bernie Jones as Punchy, a character so annoying that one of the few reasons to make it through DHR is in the hope the other characters will tire of his antics and dispatch the Swede in a hail of bullets.

Tucker went on to helm a few more burlesque films, and the 1960 sci-fi epic Cape Canaveral Monsters, a small step up from Robot Monster and Dance Hall Racket, before finding his vocation as a film editor. By contrast, Bruce became an important enough figure in the 1960s for him to figure on the cover of The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Aside from DHR, Bruce left only one other substantial gift to posterity, The Lenny Bruce Performance Film (1967), a recording of his penultimate stand-up gig in San Francisco in April 1965. The opening caption might serve as an epitaph to his life and career and perhaps even DHR: “This is not a documentary. It is a performance. Yet each of his performances was in itself a story of this man’s life.”

Commentaires

Enregistrer un commentaire