H.G. Wells . War Games

At War Control’s offices in Paris, “a series of big-scale relief maps were laid out upon tables to display the whole seat of war, and the staff-officers of the control were continually busy shifting the little blocks which represented the contending troops,” recounts H.G. Wells in his 1914 future-war novel The World Set Free. Upon these maps, Western Europe’s allied commanders intend “to play the great game for world supremacy” against their enemies. Fatally ignorant of the latest strategies of aerial warfare, not to mention the newly invented atomic bomb, supreme allied commander Marshal Dubois is scheming about entrenchments, invasions, and skirmishes when an A-bomb is dropped onto War Control’s HQ.

BANG!

It would not be unreasonable to interpret this darkly bathetic scenario as Wells’s criticism of the key role that kriegspieler — tabletop war games — played in those days as a part of military strategy and training. First developed in the mid-1600s, the modern German kriegspiel, with its topographic maps of Europe, its red and blue pieces, and its dice and statistical tables, didn’t grow popular among the Germany military until Napoleon demonstrated how much more effective than aristocrats at waging war is a professionalized elite well-versed in military science. Major German victories in 1866 and 1871 then persuaded other European nations (including Great Britain) to adopt kriegspieler as part of their own elite military training. However, when position warfare’s potential to result in slaughter on an epic scale was fully realized in the early twentieth century, it came under severe criticism from pacifists, as did the board games which turned position warfare into an abstract contest. For very different reasons, some in the military were also beginning to doubt war-games and their emphasis on position warfare. In a 1917 Harvard lecture series titled “The Warfare of To-Day,” Lieutenant Colonel Paul Azan of the French army accused kriegspieler of having prevented military strategists from seeing the way new technologies, particularly the airplane, were about to change warfare: “It thus came about that, instead of seeing things as they are, the majority of professional soldiers wandered about in a land of fancies and theories.” Ludwig Wittgenstein, while serving in an Austro-Hungarian army artillery workshop during World War I, was also disturbed by the war-game/reality disconnect; it was his superior officers’ use of kriegspieler, in fact, which inspired his famous philosophical insight that “the picture is a model of reality.”

Wells’s criticism was blunter than Wittgenstein’s, more punitive than Azan’s. In The World Set Free, the A-bomb’s blast transforms Marshal Dubois’s impressive kriegspiel into a bier or catafalque: “He was lying against a huge slab of the war map. To it there stuck and from it there dangled little wooden objects, symbols of infantry and cavalry and guns.” The advent of aerial warfare, in Wells’s opinion, had rendered obsolete the maps and symbols of military units pored over by monarchs and military strategists since the early modern era. And atomic weaponry, which Wells not only predicted but accidentally inspired (the Manhattan Project’s Leó Szilárdconceived of the nuclear chain reaction, he reported, after reading The World Set Free), would surely render obsolete much more: discrete nations, war in general.

As if the above-described grisly tableau weren’t evidence enough that Wells, a utopian who dreamed of a single world state, deplored the conflation of war with gaming, he has a visionary character in the same novel deliver a snappy epitaph for what we might call the war-gamer’sWeltanschauung. Egbert, the king of an unnamed European country, and his strategist, Firmin, have been summoned to a conference of monarchs, presidents, powerful journalists, and scientists who will confer about the state of the world. When Firmin strategizes about maintaining national autonomy and monarchical authority within the new world order, Egbert asks: “‘Don’t you think the old game’s up, Firmin?’” When Firmin argues against the “reckless … abandonment” of the old order, Egbert shuts him down: “‘BANG!’ cried the king.”

There is a certain amount of textual evidence to suggest that Wells, the son of a professional cricket player, regarded sports and other games as an impediment to the realization of a utopian future. For example, in A Modern Utopia (1905), one of his earliest and most ambitious attempts at portraying a world state, Wells has a Utopian lament to a visitor from the twentieth century about how much human energy is wasted in “unsatisfying amusements and unproductive occupations.” (“Our Founders made no peace with this organisation of public sports. They did not spend their lives to secure for all men and women on the earth freedom, health, and leisure, in order that they might waste lives in such folly.”) The elite samurai who run Utopia therefore eschew playing games in public: “‘Cricket, tennis, fives, billiards — . You will find clubs and a class of men to play all these things in Utopia, but not the samurai.’”

Of course, the “game” to which Egbert refers is by no means an unsatisfying amusement along the lines of cricket or billiards, or (for that matter) the waging of war. Though they may employ such unproductive occupations as metaphors, whenever Wells has one of his visionary characters proclaim that “the old game’s up,” or something along those lines, the “game” to which they refer is actually the Outline of History, say, or the Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind — to borrow the titles of two of Wells’s late-period nonfiction door-stoppers. Yet even this sort of world-historical gamesmanship is often derided in Wells’s writings — smacking, as it does, of grandiose delusions of omniscience and omnipotence.

In The Invisible Man (1897), for example, the rational Dr. Kemp implores the titular mad scientist not to play “a game against the [human] race”; to no avail, for the Invisible Man later declares: “The game is only beginning.” And in The War of the Worlds (1898), the narrator encounters an artilleryman whose perspective has been drastically altered by the Martian invasion. “Cities, nations, civilisation, progress — it’s all over. That game’s up,” he insists, not without some glee, for he can imagine a survivalist game at which he’d be one of the winners. The two then play a mashup of poker and kriegspiel, in which districts of London are won and lost: “Strange mind of man! that, with our species upon the edge of extermination or appalling degradation, with no clear prospect before us but the chance of a horrible death, we could sit following the chance of this painted pasteboard, and playing the ‘joker’ with vivid delight.”

The former King Egbert, however, isn’t a madman; he’s an evolved type, who shares with madmen only one characteristic: to lesser mortals, his values and worldview are alien and incomprehensible. Egbert is, in a word, a superman. (It’s worth noting here that the “supernormal” protagonist of J.D. Beresford’s 1911 The Hampdenshire Wonder, the first sci-fi novel of real importance about evolved intelligence, is loosely based on Wells, right down to the pro cricketer father.) Although Wells objected to world-historical game-playing by the insane, and to the playing of kriegspieler by regular folks, he had no objection to the gamesmanship of supermen. In fact, he wrote two books for their training — via games.

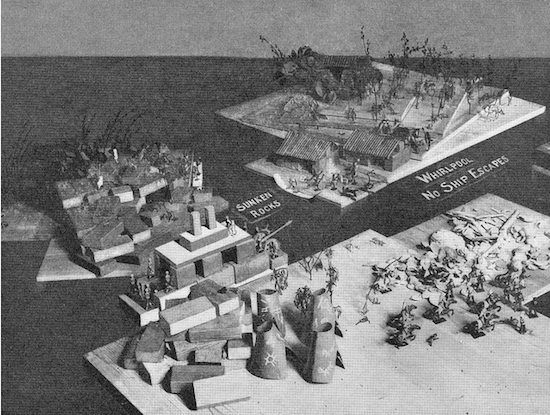

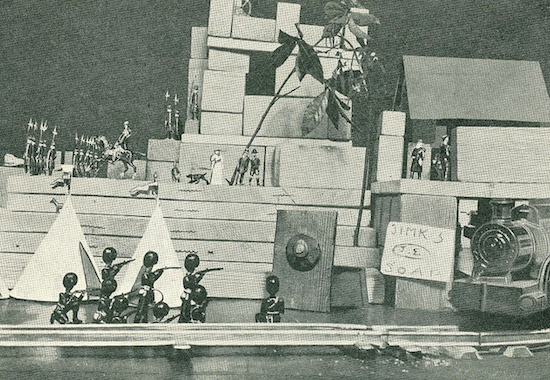

In Floor Games, a little-known volume published in 1911, when the author’s own sons G.P. “Gip” Wells and Frank R. Wells were ten and eight, respectively, Wells discusses the methodology of playing children’s floor games — with the aid of lead soldiers and other figures, wooden bricks (whose specifications are discussed in minute detail), boards, fir tree sprigs, clockwork trains and tracks, tin ships, and “those card things the cream comes in.” (Wells was asked to write the book after a publisher read his 1911 novel, The New Machiavelli, in draft and was intrigued by the town-building games of its young protagonist.) In a 1913 volume, Little Wars: A Game for Boys from Twelve Years of Age to One Hundred and Fifty and for That More Intelligent Sort of Girls Who Like Boys’ Games and Books [often rendered differently, but this appears to be the correct version], Wells offers a comprehensive guide to Little Wars (or “playroom warfare”). The latter’s appendix, titled “Little Wars and Kriegspiel,” even indicates how the Wells family’s playroom warfare might be developed into… a board game.

Parenthetically, Wells was not the only Edwardian author to write about elaborate playroom civilizations. His friend E. Nesbit’s 1913 book, Wings and the Child: Or, the Building of Magic Cities, uses themes developed in both her 1901 story “The Town in the Library in the Town in the Library” and her novel The Magic City (1910) as a springboard to discuss childhood psychology and education. Nor, though he claims to be the inventor and chief practitioner of playroom warfare, was Wells the first to pen a guide to playing detailed wars with model soldiers. In the two decades prior to the outbreak of World War I, there was a toy soldier craze in Britain. An 1898 magazine article mined the notebooks of the recently deceased Robert Louis Stevenson to give a blow-by-blow account of a tin soldier war that he waged with his stepson, though the earliest how-to manual for playroom warfare of which I’m aware is a little-known 1910 book by A.J. Holladay titled War Games for Boy Scouts: Played with Model Soldiers.

Unlike Nesbit, not to mention child psychologists who study play, Wells displayed no interest in what floor games and playroom warfare reveal about children’s deepest thoughts and feelings. (It is a historical irony that British pediatrician Dr. Margaret Lowenfeld was inspired by Floor Gamesto develop a child treatment modality known as the World Technique, which in turn inspired the Swiss Jungian therapist Dora M. Kalff’s “sandplay” method.) Sons “G.P.W.” and “F.R.W.” are described in Floor Games and Little Wars as peers of author H.G.W., and when it comes to intelligence, quick wit, and imagination, even his superiors.

Though Wells’s approach is closer to that of Holladay or Stevenson (who, by the way, wrote not one but two poems about toy soldiers), the games that he describes aren’t strictly military in nature. Wells takes pains, in the conclusion to Little Wars, to argue against “Great War,” which is to say, against actual warfare: “All of us in every country, except a few dull-witted, energetic bores, want to see the manhood of the world at something better than apeing the little lead toys our children buy in boxes.” True, when the Great War began, Wells seemed to change his tune, becoming violently anti-German and anti-pacifist; in his defense, he hoped it would be the war to end all wars. As professional game designers who’ve penned introductions or afterwords to recent facsimile editions of one or both of the books have pointed out, Wells’s games are exercises in expanding the capacities of the imagination.

Greg Costikyan, award-winning creator of 1980s role-playing games like Paranoia and Pax Britannica, argues in a 1995 introduction to Little Wars that the game’s simple rules indicate that Wells “was not striving to perfect the definitive military simulation of his day.” In the game, “combat” is a matter of aiming and discharging a spring breech-loader gun; “mêlée” is resolved by a one-to-one exchange of losses, with the modification that the superior force preserves as many additional men, and suffers as many fewer casualties, as its superiority; and there is a movement limit of one foot per turn for infantry and two per cavalry. The main appeal of Little Wars, therefore, writes Costikyan, is “the appeal to intellectual engagement.”

Wells concludes Little Wars by noting that Great War is “a game all out of proportion,” in part because “the available heads we have for it, are too small.” In Wells’s 1913 romance novel The Passionate Friends, the narrator concludes with a moral that scandalized his small-headed countrymen, but which he must have hoped would one day resonate with the big-headed future supermen and samurai who’d grown up playing his open-ended games: “I know that a growing multitude of men and women outwear the ancient ways. The blood-stained organized jealousies of religious intolerance, the delusions of nationality and cult and race, that black hatred which simple people and young people and common people cherish against all that is not in the likeness of themselves, cease to be the undisputed ruling forces of our collective life. We want to emancipate our lives from this slavery and these stupidities, from dull hatreds and suspicion. The ripening mind of our race tires of these boorish and brutish and childish things.” The old game, that is to say, is up.

Unlike the insane visionary, who sees society, culture, the economy, politics, and so forth as a game whose rules are misunderstood by all but an elite few, the Wellsian superman regards the very same phenomena as a game the rules of which are reinvented again and again over the years. To all but an elite few, the reinvented rules eventually come to seem natural, permanent, and inevitable. Exactly like his science fiction, the effect of Wells’s Floor Games and Little Wars is to inoculate as many of us as possible against that eventuality.

Commentaires

Enregistrer un commentaire